Admit it: At one point or another, you have probably said something unpleasant online that you later regretted — and that you wouldn’t have said in person. It might have seemed justified, but to someone else, it probably felt inappropriate, egregious or like a personal attack.

In other words, you were a troll.

New research by computer scientists from Stanford and Cornell universities suggests this sort of thing — a generally reasonable person writing a post or leaving a comment that includes an attack or even outright harassment — happens all the time. The most likely time for people to turn into trolls? Sunday and Monday nights, from 10pm to 3am.

Trolling is so ingrained in the internet that, without even noticing, we’ve let it shape our most important communication systems. One reason Facebook provides elaborate privacy controls is so we don’t have to wade through drive-by comments on our own lives.

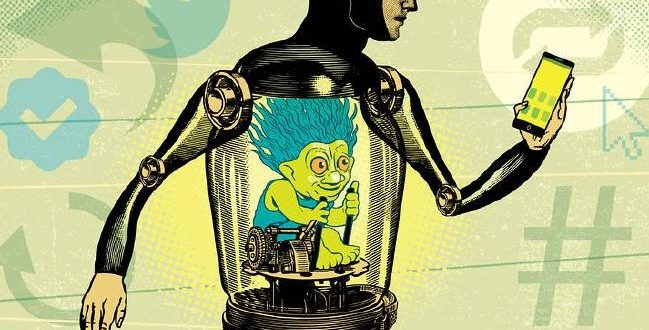

Countless media sites have turned off comments rather than attempt to tame the unruly mob weighing in below articles. Others have invested heavily in moderation, and are now adopting tools like algorithmic filtering from Jigsaw, a division of Google parent Alphabet Inc., which uses artificial intelligence to determine how toxic comments are. YouTube and Instagram both have similar filtering. (Snapchat is, arguably, built around never letting trolls see or give feedback on your posts in the first place.)

Then there’s the one real public commons left on the internet — Twitter, which is in a pitched battle with trolls that, on most days, the company appears to be losing.

But if the systems we use are encouraging us to be nasty, how far can developers go to reverse the trend? Can we ever achieve the giant, raucous but ultimately civil public square that was the promise of the early internet?

“It’s tempting to believe that all the problems online are due to someone else, some really sociopathic person,” says Michael Bernstein, an expert in human-computer interaction at Stanford University, and one of four collaborators on the research. “Actually, we all have to own up to this.”

Diehard internet trolls do exist and may instigate trolling in others, these researchers say. Harassment, stalking, threats of violence, psychological terrorism and serially abusive behaviour online are real and must be stopped. But by focusing on the most egregious repeat offenders, internet companies have missed the forest for the trees.

A significant proportion of trolling comes from people who haven’t trolled before, the researchers say. To determine this, they analysed 16 million comments from CNN’s website. The researchers defined trolling as swearing, harassment and personal attacks, but emphasise that trolling is defined by the community and differs from one to the next.

One thing that drives people to troll is, unsurprisingly, their mood. Studies have shown that people’s moods, as revealed by the tone of their posts on Twitter, follow a remarkably predictable pattern: Relatively positive in the morning, and more negative as the day wears on. You can guess the weekly pattern: Mondays are the worst, and people seem to feel better on the weekend.

There’s an almost identical circadian rhythm for trolling, according to the research team.

The researchers also uncovered a pile-on effect. Being trolled in another comment thread, or seeing trolling further up in a thread, makes people more likely to join in, regardless of the article’s content. Based on this, it’s easy to see how committed trolls could inspire — or really infect — others. It’s not so different from a real-world mob, only on the internet it’s much easier to find yourself in the midst of one.

In a controlled experiment, the Stanford and Cornell researchers established that together, mood and exposure to trolling can make a person twice as likely to troll.

Internet companies don’t have much power over our mood swings. But they do control the design of the systems they create. Far from operating neutral “platforms” for online discussion, they can shape the discussions they host. We already know we feel a psychological distance from others when communicating through screens and keyboards. When these companies fail to accept and act on their responsibility, they are in essence encouraging our most impulsive, hostile and anti-social tendencies.

Luckily, there are solutions that go beyond the expensive and not very scalable one that community managers have long relied on, live human moderators. In February, Twitter rolled out a new feature that, for about a 12-hour period, blocks the tweets of an abusive user, as determined by Twitter’s algorithms, from being seen by anyone but the harasser’s followers. More recently, Twitter has taken steps to identify accounts that were obviously spawned to harass others.

Both Facebook and Google have their own systems for flagging abusive behaviour and an escalating ladder of punishments for those who commit it. Jigsaw recently rolled out its AI, but a person familiar with the workings of the system said that it remains far from perfect, generating many false positives. So it’s still up to the user to wade through the comments it flags.

Even a perfect “penalty box” approach to comment moderation doesn’t go far enough. The internet needs ways to encourage users’ empathy and capacity for self-reflection, which are more lasting antidotes to online hostility.

Software from Civil, a Portland start-up, forces anyone who wants to comment to first evaluate three other comments for their level of civility. Initially, the third comment people are asked to review is their own, which they have the option to revise — and they often do, according to Civil co-founder Christa Mrgan. In this way, the system accomplishes the neat trick of helping readers see their words as someone else would.

A site published by the Norwegian public broadcaster NRK just rolled out a system that gives readers a brief multiple-choice quiz about the contents of an article — proving they really read it — before allowing them to comment.

Social networks, publishers and other platforms have an obligation to think not merely about how to cope with online abuse, but about how to elevate the level of the discussions they host. While it’s more of a possibility than ever — especially with the rise of AI — the question is, how motivated is the tech industry to accomplish it?

Reader comments on this site are moderated before publication to promote lively and civil debate. We encourage your comments but submitting one does not guarantee publication. We publish hundreds of comments daily, and if a comment is rejected it is likely because it does not meet with our comment guidelines, which you can read here. No correspondence will be entered into if a comment is declined.