Putting up a TV antenna is one of the best steps you can take to breaking your reliance on pay TV. Most areas of the U.S. have access to several dozen TV channels broadcast over the air for free.

A TV antenna will bring them to your TV, so you won’t be stuck with the “local broadcast TV fee” charged by your cable or satellite company. And if you decide to subscribe to an online TV provider, you won’t need to worry about which ones carry your local channels (not all of them do).

As a bonus, they’ll make your big-screen TV shine with a better picture than cable or satellite can deliver. This is possible because those transmissions are typically compressed in order to preserve bandwidth, so the service providers can cram more channels into their pipes (many of which you probably don’t even care to watch).

You’ll notice the difference in quality on the major broadcast networks mostly, because all of them broadcast in high definition. Most stations broadcast a 1080i (interlaced scanning) signal, which is the highest resolution currently used for OTA TV in the US, but a handful transmit at 720p (progressive scanning). Both specs are considered to be high definition.

Here’s our five-step guide to choosing the right TV antenna:

- Determine which channels are available where you live

- Choose which channels you want to watch

- Checke the rules on antenna installation where you live

- Figure out which type of antenna you need

- Select the antenna

Which channels are available on an antenna?

The first step to choosing a TV antenna is figuring out which channels are available where you live and of those, which ones you want to watch.

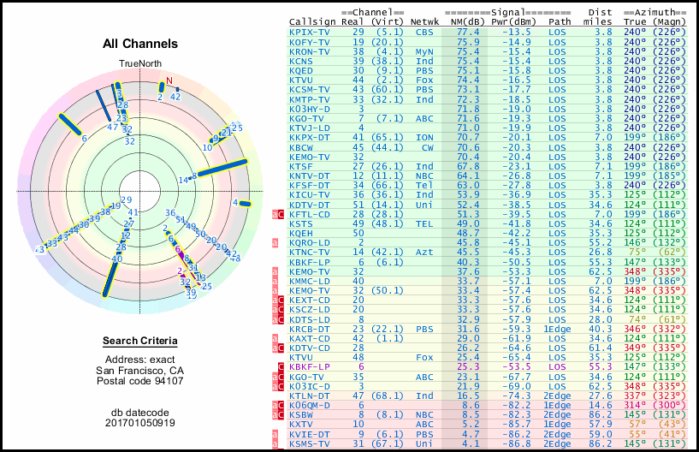

To figure out what’s on air where you live, head over to TV Fool. It pairs the FCC’s broadcast TV database with topographical maps to give you a pretty detailed estimation of which signals will reach your house and how strong they’ll be.

Enter your house address in the search box, hit enter, and you’ll get something like this in return:

Martyn Williams/IDG

Martyn Williams/IDGA screenshot of the TV Fool website showing television reception in San Francisco.

That chart above looks pretty complicated, but it’s really not.

Which channels do I want to watch?

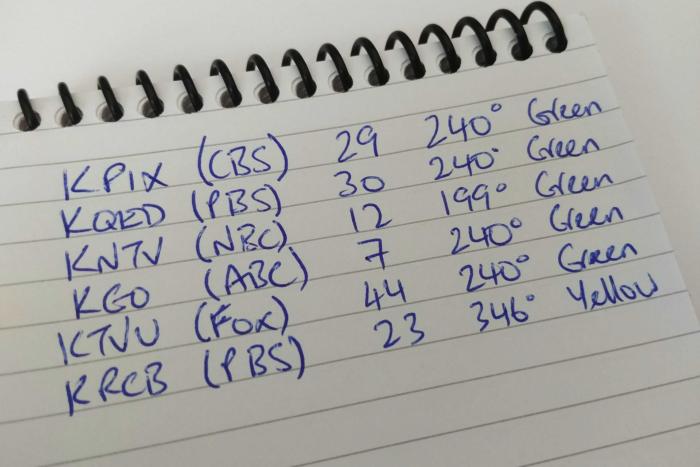

At this point, it might be a good idea to check the TV guide in a newspaper or website to determine what’s on air and what you want to watch. Make sure you choose “antenna” or “over the air” as your TV provider in the online program guide, so you don’t get cable channels mixed in.

Many TV stations broadcast several channels as a digital package, so make sure to look at those as well.

Once you’ve made your list, examine the TV Fool results to find the channels you want to watch. Write down the number in the second column, the “real channel,” the second-to-last column, the “true azimuth,” and the color (green yellow, or red). The colors will inform you if an indoor antenna will be sufficient, or if you’ll need an attic or roof-mounted model to pull them in.

Martyn Williams/IDG

Martyn Williams/IDGTV channels

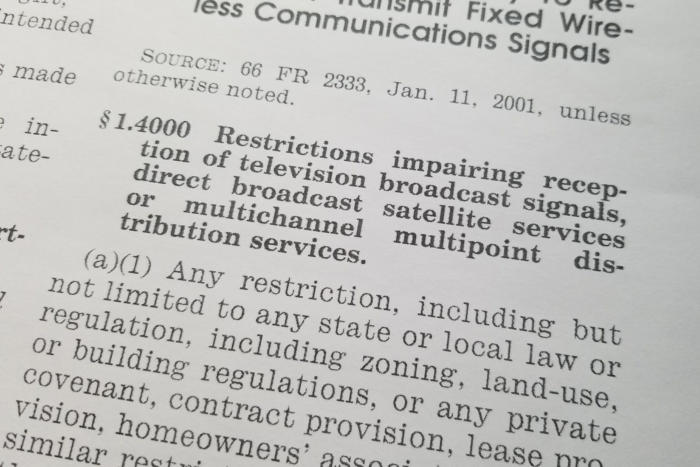

Can I put up an antenna?

In almost all cases, the answer is yes. The FCC’s over-the-air reception devices (OTARD) rule gives you the right to erect an antenna for the reception of over-the-air TV or satellite programming. It applies to both homeowners and renters, and it overrides the power of home-owners associations (HOAs) to block antenna deployments.

The rule covers antennas required for an “acceptable quality signal” on your property, or if you rent, an area where you have exclusive use. The FCC website has full details.

Martyn Williams/IDG

Martyn Williams/IDGThe FCC’s OTARD rule.

Which antenna do I need?

TV Fool ranks station in order of predicted signal power, with the easiest to receive at the top. The green channels can probably be received with a simple indoor antenna, yellow ones will probably require a larger antenna in an attic space or on the roof, and the red ones will require a good roof-mounted antenna.

Indoor antennas are typically flat, so they’re easy to set up, usually by hanging them in a window on the side of the house facing the transmitter. Some look different, a bit like the old ‘rabbit ears’ antennas or even like a soundbar, but the principle is the same: install them in a favorable location.

Indoor antennas are typically fine for all the strong local channels, but if you want channels that are weaker or further away, you might need to go larger and put an antenna in your attic space or on your roof.

Compared to the roof, an antenna in the attic will probably receive slightly less signal because it’s enclosed, but it might be enough to get stable TV reception. If you hate the look of an outdoor antenna, then experiment. An attic-mounted antenna will also be easier to maintain.

RCA

RCAThe RCA Skybar is designed to resemble a soundbar and can be mounted beneath a wall-hung flat-screen.

The direction of the TV transmitter tower is also important. If you’re using an indoor antenna, you’ll want to put it in a window facing that direction. If you’re using an outdoor antenna, it will show you which way to point. As signals get weaker, going from green to yellow to red, the direction is more important. If you want to tune in weaker stations from towers in different directions, you’ll probably need a rotator. This motorized device will turn the antenna so that it’s oriented to pull in those weaker signals.

Knowing the real channel number will help you select an antenna. TV broadcasting in North America is spread across three frequency bands: low VHF (channels 2 through 6), high VHF (channels 7 through 13), and UHF (channels 14 through 50). Because of the different frequencies in use, antennas are designed to cover one, two or three bands. Not every antenna covers them all.

Sean MacEntee (CC BY 2.0)

Sean MacEntee (CC BY 2.0)TV antennas.

The real channel number helps you figure this out. After TV stations went digital, some no longer transmit on the channel number they announce on air. For example, channel 5 in San Francisco is actually broadcasting on channel 29. That’s why the real channel is important in antenna selection.

Be prepared to put up with a lot of marketing speak when checking out antennas. For the record, there is no such thing as an “HD” antenna or “digital” antenna–the format of the signals being received doesn’t matter–and take those “miles” range claims in the product specifications with a grain of salt. No manufacturer can guarantee their antenna will pull in a signal from a given number of miles because too much depends on local topology, signal strength, interference, and other factors unique to your location.

Having said that, those range claims are useful in evaluating antennas from the same manufacturer. It’s a good bet that an antenna labeled that claims 65 miles of range is generally better for long-distance reception than one from the same company that claims to deliver 30 miles of range.

Analyzing your list

In the example above, an indoor antenna will probably pull in all the green channels coming from the transmitter at 240 degrees, and the same antenna will also likely work for the third channel in the list, which comes from a different transmitter at 199 degrees, but has a strong signal.

The last station on the list will require a bit more work. A larger antenna is probably required, and because it’s more than 100 degrees from the others, it will probably require a second antenna or a rotator.

Now is the time to ask yourself if that sixth channel is worth the extra equipment and installation.

Finally, look at those channel numbers. In the list, two channels are high VHF (12 and 7) and the rest are UHF, so you’ll need an antenna that covers both those bands.

Do I need a signal amplifier or a rotator?

If you’re unable to receive distant TV stations due to low signal levels, you should consider a signal amplifier. It’s always best to collect as much signal as possible at the antenna, so don’t skimp on a small one and try to make up for it with an amplifier. But if a large antenna still won’t pull in the station without picture break-up, a signal amplifier might help. You also might need one if you have an excessively long run of cable, say from a distant spot on a piece of land to a house.

A rotator will turn the TV antenna in any direction with the click of a remote. These are useful if you want to receive stations from several different locations.

Martyn Williams/IDG

Martyn Williams/IDGA TV antenna with rotator installed.

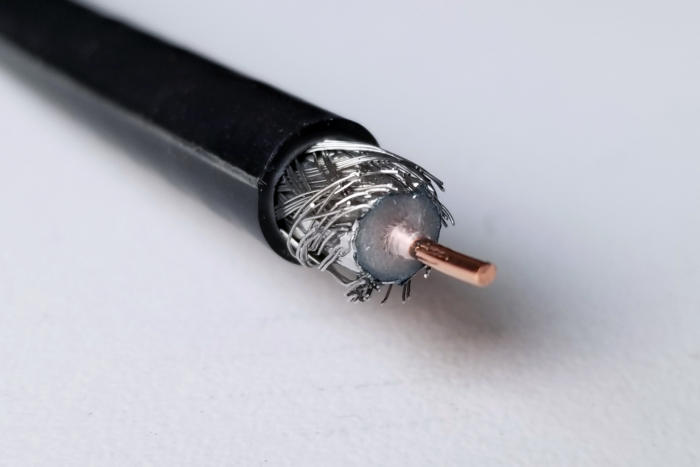

What type of cable do I for a TV antenna?

The connection from your antenna to your TV is every bit as important as the antenna itself. You need a high-quality coaxial cable (“coax” for short) for the job. Coax has a center wire that carries the signal and is surrounded by a plastic insulator. Then there’s an outer braid that shields the center cable from interference, and an outer sheath to protect the cable from the elements.

Don’t be tempted to save a few dollars reusing old coax. Buy new coax in the length you need. Try to avoid coupling two cables together, as each union will result in a little signal loss. The most common type of cable for TV is called RG-6.

Martyn Williams/IDG

Martyn Williams/IDGA piece of coaxial cable cut and ready for a connector to be attached.

A final word of advice

Predicting which antenna will work with certainty is almost impossible. The information garnered from sites like TV Fool will provide a strong indication of what should work, but there are other variables at work.

In some areas, especially in cities or areas with lots of hills, signals can bounce off obstacles like buildings and cause interference, trees can grow leaves in the spring and block stations you got fine in the winter, and atmospheric conditions can alter the way signals reach your house.

Moving an antenna just a little to one side or up and down a window can have a big effect on reception. If you’re putting up an external antenna, one side of your roof might bring in nothing while the other side provides perfect reception.

Be prepared to experiment.

This story, “How to choose a TV antenna” was originally published by

TechHive.